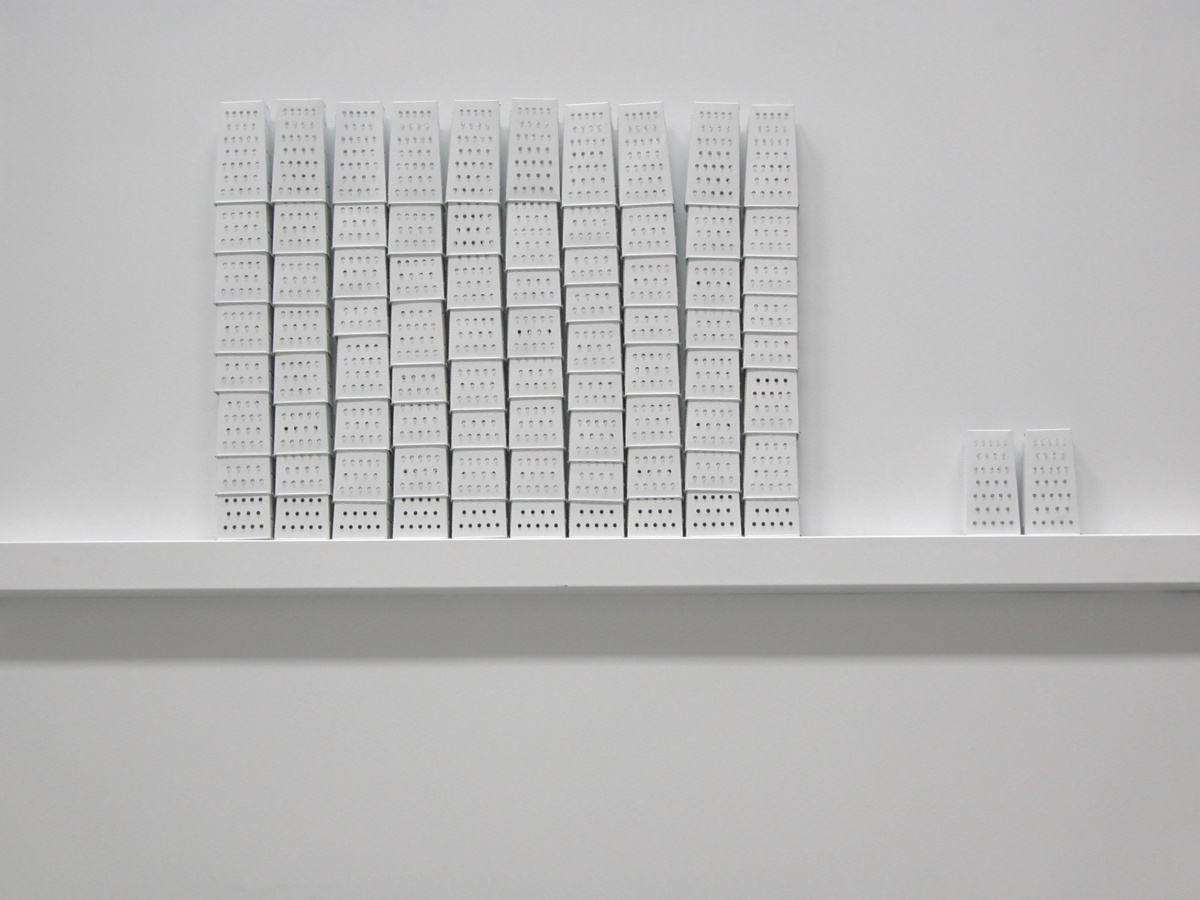

Il lavoro artistico di Massimo Antonelli cerca d’indagare ed interpretare la realtà esistente. Al di là di ogni singolo lavoro, sono il pensiero e la ricerca di Antonelli ha creare una continuità di visione e di riflessione. La scoperta dell’oggetto (la grattugia), il prelievo, e la sua espansione come modulo che invade l’ambiente hanno dilatato il processo di percezione e la sua posizione critica verso il mondo.

Alcune sue strutture che sono riconducibili alla città ad esempio New York, non lo sono solamente per un fatto formale o estetico, ma per l’interesse sempre manifestato dall’artista per l’architettura intesa come proiezione intellettuale che tende ad un mondo migliore. L’arte contemporanea, da alcuni anni converge e si mescola con altri linguaggi come l’architettura e l’urbanistica.

Una relazione e un confronto tra artisti, architetti, filosofi, urbanisti con un rinnovato impegno di analisi e polemica politico-sociale. Massimo Antonelli ha anticipato questa tendenza sia come regista cinematografico e parallelamente come artista visivo. Il riferimento a Marcel Duchamp è quasi obbligato ma il lavoro artistico di Massimo Antonelli è più vicino a ManRay. I due artisti cercano di stabilire un contatto poetico con l’oggetto, scavalcando il suo momento pratico.

Massimo Antonelli e Man Ray ridimensionano democraticamente il mito stesso della creazione che Duchamp fino alla fine ha alimentato. Il pane celeste o la scopa dipinta di Man Ray riconducono a la grattugia gialla o ai cestelli della lavatrice in colori diversi di Antonelli, oggetti che però, non vogliono ghermire o appropriarsi della realtà come per esempio nel caso di Jasper Johns, La ricognizione nel reale anche se precisa e lucida è sempre poetica in Massimo Antonelli.

In questo artista convivono aspetti complementari e divergenti. L’utilizzo di Massimo Antonelli delle cosiddette “strutture primarie” ci sposta nell’area della “minimal art” (arte realizzata con mezzi minimi). E’ ovvio che le sue strutture non sono solo “pure presenze” ma anche Antonelli si avvale della serialità e dell’utilizzo di un modulo. E’ dalla ripetizione stessa che si deve e si può condensare una ragione, una risposta fisica o metafisica. Massimo Antonelli lascia libere le sue strutture di vagare per lo spazio, evocare significati lirici e scoprire nuove dimensioni, ma è sempre alla ricerca continua e spinto dalla volontà di trovare un senso alle sue opere.

Massimo Antonelli regista, sceneggiatore e pittore nato ad Asmara nel 1942, molisano d’adozione, vive a Campobasso fino a vent’anni, poi si stabilisce e lavora a Roma. Tra il 1967 e il 1969 frequenta il Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia sotto la guida di Roberto Rossellini. Collabora come aiuto regista a diversi lavori cinematografici e teatrali. Realizza come regista e sceneggiatore il film: “Tema di Marco” che vincerà la Targa “Leone d’Argento” nella sezione Stampa Estera alla 32a Mostra del cinema di Venezia. Tra il 1979 e il 2005 collabora con la Rai – Radio Televisione Italiana realizzando servizi televisivi e regie. Come “film-maker” realizza e produce film e film d’indagine. Dal 2002 ad oggi Massimo Antonelli espone in diverse personali e collettive, a Roma, Lugano, Napoli, Cremona e Lisbona, i suoi lavori sono presenti in numerose collezioni private e diversi Musei Italiani e stranieri.

Il critico d’arte Germano Celant ha sottolineato più volte il primato dell’architettura rispetto ad altre categorie estetiche e discipline artistiche. Molti artisti proiettano il loro lavoro nella dimensione dei grandi spazi. Basta pensare alla “Land Art” interventi artistici sul territorio o alle strutture nel cielo, grandi bolle trasparenti, dell’artista Saraceno che immagina città sospese nell’aria con la sostanza da lui elaborata l’”aereogel”.

L’interesse all’urbanistica è strettamente legato ad una società in continua evoluzione. Nel tuo lavoro c’è sempre stato un coinvolgimento verso la condizione sociale ed umana del singolo individuo. Ma invece di sforzarti ad inventare dimensioni alternative e ambienti utopici più confortevoli, ti sei concentrato sulla vita reale delle persone nelle città, come per esempio nella tua ultima installazione al Museo Colonna con dei cilindri di lavatrici detti cestelli: “nuove periferie urbane ed extra urbane”. E’ come se volessi avvertire che non t’interessa la natura o l’ecologia e neppure ipotizzare spazi fantastici futuribili, è l’uomo che sopravvive isolato nel grattacielo della periferia su cui dobbiamo concentrarci.

Le Corbusier ha creato spazi diversi nella natura. Oggi non è più ipotizzabile. E’ vero non mi è mai interessato l’aspetto ecologico, la vera giungla è la periferia di Roma, dove continuo a tornare per capacitarmi del fatto di come si possa vivere in quell’inferno piuttosto che in campagna. Una volta quei posti erano occupati da boschi e campi. Ma non è nostalgia per un eden perduto ma empatia verso la condizione del singolo individuo. La lavatrice usata nella mia installazione è un simbolo. Dove si lavano i panni sporchi: le nostre coscienze e tutto è disgregato, fagocitato. A volte mi sembra ancora di sentire il grido della Magnani in “Mamma Roma” di Pasolini, lui aveva già previsto e capito tutto, tanto tempo prima di altri.

C’è sempre stato uno scambio cruciale tra arte figurativa e cinema silenzioso ma continuo. La pittura è assunta come documento estetico oppure è un film che vuole essere un immenso affresco. Basta pensare a Visconti o a Bertolucci. Il sogno di molti artisti è di poter fare un giorno un film: la sintesi di tutte le arti. Massimo Antonelli ha fatto l’uno e l’altro. Ed esiste un filo conduttore tra il suo lavoro visivo e quello cinematografico, che è rappresentato dai contenuti espressi, oltre che da una grande attenzione iconografica e di elaborazione dello spazio. Questo scambio continua?

Certamente a livello intellettuale e visivo lo scambio arte e cinema non è mai cessato per me. Umanamente invece provoca un dualismo che non riesco a risolvere, forse l’artista fugge in avanti e per il cinema rimane qualcosa d’incompiuto, qualcosa che devo trovare, forse solo per me stesso, non voglio dimostrare nulla agli altri.

Gli artisti che escono dall’ambito tradizionale della scultura o della pittura come nel caso di Massimo Antonelli e invadono l’ambiente, tendono ad accorciare il confine fra arte e vita, fino ad arrivare agli artisti che si sono prolungati nell’azione. Ma oggi secondo il tuo parere, ha ancora senso il rifiuto dell’artista di produrre “oggetti” in quanto mercificabili, oppure all’estremo opposto ritornare alla performance per vendere la propria immagine a caro prezzo?

Una frase di Andy Warhol rimane emblematica: “Gli artisti producono cose inutili che alcuni apprezzano e sono disposti a comperare”.

In Andy Warhol c’è la ripetizione nel quadro della stessa immagine fino a cinquanta, duecento volte. Qualcosa di simile al meccanismo ripetuto dei suoi film, dove la stessa inquadratura o la visione dello stesso oggetto veniva protratta per un tempo indefinito. La rivoluzione vera e propria è nella sostituzione dell’immagine dipinta con l’immagine fotografica. Questo distacco non ti accomuna certo a Warhol, ma anche nel tuo caso c’è l’ossessione e la ripetizione del medesimo oggetto: la grattugia.: Come la interpreti?

La grattugia è un “modulo” ma è anche un modo per poter essere infantile senza sensi di colpa, continuare il gioco sul serio. Non è feticismo e neppure un marchio di riconoscimento; Fontana non è solo il taglio.

Schifano guardava la realtà che riproduce nei suoi quadri come se fosse stato sempre dietro uno schermo o un finestrino di un’automobile. L’artificio e il vero si confondono. Chi ha inquadrato il mondo da un obbiettivo come interpreta la dimensione reale?

Schifano come molti altri artisti dell’avanguardia aveva anticipato un modo di fare arte con grande anticipo, mentre io ero distratto a fare cinema. Il cinema per lui era una lente d’ingrandimento. E’ così che il contenuto diventa mezzo espressivo.

Tra vent’anni si è ipotizzato un panorama per l’Italia molto simile al Brasile; un paese diviso tra una minoranza sempre più ricca e una maggioranza sempre più povera. Lo Stato sarà costretto ad attingere alla Cultura, prima di toccare l’Istruzione o la Sanità, come il nostro Governo sta già facendo. Come si colloca l’artista in questo contesto e il ruolo di Massimo Antonelli?

Una volta credevo nel Socialismo reale, oggi non più. La vera unica rivoluzione nasce dal singolo individuo e dalle sue scelte, dall’esempio di ognuno di noi. Sono un anarchico, ma che vuole creare non distruggere, assumendomi le mie responsabilità fino in fondo. E poi salviamo i dubbi, non ho mai creduto nelle certezze assolute di nessun tipo.

Nella didattica scolastica per chi si occupa d’arte e di estetica non pensi sia necessario aggiungere oltre alla Storia dell’arte anche la Storia del Cinema per studiare i grandi capolavori e i registi di questo secolo?

Ho sempre tentato di fare qualcosa di concreto in proposito con scarsi risultati. Se solo si capisse l’importanza del cinema non solamente come storia, linguaggio e valore artistico ma soprattutto come di un mezzo capace di aprire la mente; a questo proposito Lattuada credeva che se un giorno una pellicola fosse costata come un rasoio elettrico o una penna stilografica, sarebbe stato un passo decisivo verso la vera libertà. La cosa buffa, paradossale, è che oggi tecnologicamente e come costi si è arrivato a questo ma per completare quel sogno manca una storia da raccontare. Almeno io la cerco ancora.

Interview by Cristina Ruffoni

Massimo Antonelli’s artistic work seeks to investigate and interpret existing reality. Beyond each single work, Antonelli’s thought and research have created a continuity of vision and reflection. The discovery of the object (the grater), its removal, and its expansion as a module that invades the environment have expanded the process of perception and its critical position towards the world.

Some of his structures that can be traced back to the city, for example New York, are not only so for a formal or aesthetic reason, but for the interest always shown by the artist in architecture understood as an intellectual projection that tends towards a better world. Contemporary art has been converging and mixing with other languages such as architecture and urban planning for some years.

A relationship and a comparison between artists, architects, philosophers, urban planners with a renewed commitment to analysis and political-social controversy. Massimo Antonelli anticipated this trend both as a film director and simultaneously as a visual artist. The reference to Marcel Duchamp is almost obligatory but Massimo Antonelli’s artistic work is closer to ManRay. The two artists try to establish a poetic contact with the object, bypassing its practical moment.

Massimo Antonelli and Man Ray democratically resize the very myth of creation that Duchamp nurtured to the end. The light blue bread or the painted broom by Man Ray lead back to the yellow grater or the washing machine baskets in different colors by Antonelli, objects which, however, do not want to seize or appropriate reality as for example in the case of Jasper Johns, La reconnaissance in the real even if precise and lucid it is always poetic in Massimo Antonelli.

In this artist, complementary and divergent aspects coexist. Massimo Antonelli’s use of the so-called “primary structures” moves us into the area of “minimal art” (art created with minimal means). It is obvious that his structures are not only “pure presences” but Antonelli also makes use of seriality and the use of a module. It is from repetition itself that a reason, a physical or metaphysical response must and can be condensed. Massimo Antonelli leaves his structures free to wander through space, evoke lyrical meanings and discover new dimensions, but he is always continuously searching and driven by the desire to find meaning in his works.

Massimo Antonelli, director, screenwriter and painter, born in Asmara in 1942, Molise by adoption, lived in Campobasso until he was twenty, then settled and worked in Rome. Between 1967 and 1969 he attended the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia under the guidance of Roberto Rossellini. He collaborates as assistant director on various cinematographic and theatrical works. He directed and wrote the film: “Tema di Marco” which won the “Silver Lion” award in the Foreign Press section at the 32nd Venice Film Festival. Between 1979 and 2005 he collaborated with Rai – Radio Televisione Italiana creating television reports and directions. As a “film-maker” he creates and produces films and investigative films. From 2002 to today Massimo Antonelli has exhibited in various solo and collective exhibitions in Rome, Lugano, Naples, Cremona and Lisbon; his works are present in numerous private collections and several Italian and foreign museums.

The art critic Germano Celant has repeatedly underlined the primacy of architecture compared to other aesthetic categories and artistic disciplines. Many artists project their work into the dimension of large spaces. Just think of the “Land Art”, artistic interventions on the territory or the structures in the sky, large transparent bubbles, by the Saraceno artist who imagines cities suspended in the air with the substance he developed, “aerogel”.

Interest in urban planning is closely linked to a continually evolving society. In your work there has always been an involvement towards the social and human condition of the individual. But instead of forcing yourself to invent alternative dimensions and more comfortable utopian environments, you focused on the real life of people in cities, as for example in your latest installation at the Colonna Museum with washing machine cylinders called baskets: “new urban and extra-urban suburbs ”. It’s as if you wanted to warn that you’re not interested in nature or ecology or even hypothesizing fantastic futuristic spaces, it’s the man who survives isolated in the suburban skyscraper that we need to focus on.

Le Corbusier created different spaces in nature. Today it is no longer conceivable. It’s true I’ve never been interested in the ecological aspect, the real jungle is the outskirts of Rome, where I keep returning to understand how one can live in that hell rather than in the countryside. Once those places were occupied by woods and fields. But it is not nostalgia for a lost Eden but empathy towards the condition of the single individual. The washing machine used in my installation is a symbol. Where dirty clothes are washed: our consciences and everything is disintegrated, engulfed. Sometimes I still seem to hear Magnani’s cry in Pasolini’s “Mamma Roma”, he had already foreseen and understood everything, long before others.

There has always been a crucial exchange between figurative art and silent but continuous cinema. The painting is taken as an aesthetic document or it is a film that wants to be an immense fresco. Just think of Visconti or Bertolucci. The dream of many artists is to be able to make a film one day: the synthesis of all the arts. Massimo Antonelli did both. And there is a common thread between his visual work and his cinematographic work, which is represented by the contents expressed, as well as by a great attention to iconography and the elaboration of space. Does this exchange continue?

Certainly on an intellectual and visual level the exchange of art and cinema has never ceased for me. Humanly, however, it causes a dualism that I cannot resolve, perhaps the artist flees forward and something remains unfinished for cinema, something that I have to find, perhaps only for myself, I don’t want to prove anything to others.

Artists who leave the traditional sphere of sculpture or painting, as in the case of Massimo Antonelli, and invade the environment, tend to shorten the boundary between art and life, up to the artists who have continued their action. But today, in your opinion, does it still make sense for the artist to refuse to produce “objects” as they are commodifiable, or at the other extreme to return to performance to sell one’s image at a high price?

A phrase by Andy Warhol remains emblematic: “Artists produce useless things that some appreciate and are willing to buy.”

In Andy Warhol there is repetition of the same image in the painting up to fifty, two hundred times. Something similar to the repeated mechanism of his films, where the same shot or vision of the same object was continued for an indefinite time. The real revolution lies in the replacement of the painted image with the photographic image. This detachment certainly doesn’t connect you to Warhol, but in your case too there is the obsession and repetition of the same object: the grater: How do you interpret it?

The grater is a “module” but it is also a way to be childish without guilt, to continue the game seriously. It is not fetishism nor even a mark of recognition; Fontana isn’t just about cutting.

Schifano looked at the reality that he reproduces in his paintings as if he had always been behind a screen or a car window. Artifice and reality are confused. How does someone who has framed the world through a lens interpret the real dimension?

Schifano, like many other avant-garde artists, had anticipated a way of making art well in advance, while I was distracted making films. Cinema for him was a magnifying glass. This is how content becomes a means of expression.

In twenty years, a panorama for Italy very similar to Brazil has been hypothesized; a country divided between an increasingly rich minority and an increasingly poor majority. The State will be forced to draw on Culture, before touching Education or Healthcare, as our Government is already doing. How does the artist fit into this context and the role of Massimo Antonelli?

I once believed in real Socialism, today I no longer believe. The only true revolution arises from the individual and from his choices, from the example of each of us. I am an anarchist, but one who wants to create not destroy, taking on my responsibilities to the full. And then let’s save the doubts, I have never believed in absolute certainties of any kind.

In school teaching for those who deal with art and aesthetics, don’t you think it is necessary to add the History of Cinema in addition to the History of Art to study the great masterpieces and directors of this century?

I have always tried to do something concrete about it with little success. If only we understood the importance of cinema not only as history, language and artistic value but above all as a medium capable of opening the mind; in this regard Lattuada believed that if one day a film cost as much as an electric razor or a fountain pen, it would be a decisive step towards true freedom. The funny, paradoxical thing is that today technologically and in terms of costs we have achieved this but to complete that dream there is no story to tell. At least I’m still looking for it.